Adam Clausen

From 213-year sentence to community leadership

The system did not offer a release mechanism when Adam began serving his sentence. Judges imposed determinate sentences, and “truth in sentencing” laws required individuals to serve at least 85 percent of their time. In Adam’s case, the judge sentenced him to 213 years in federal prison. Under that draconian sentencing system, Adam was expected to serve more than 181 years, considering he earned all the Good Conduct Time possible.

Instead of losing hope, Adam adhered to the principles we write about in our course, Preparing for Success after Prison.

What Brought Adam to Prison:

Like many people in prison, Adam acknowledges that his bad decisions began during childhood. Rather than listening to teachers and positive role models, he built friendships with other at-risk youth with whom he began using and selling drugs and burglarizing homes and businesses.

While his peers advanced through high school, Adam instead dropped out and left home. His criminal lifestyle quickly caught the attention of local law enforcement, which led to his arrest for burglary and robbery. Facing first time felony charges at the age of 18, a county court judge sentenced him to 12 years in state prison.

After just three and half years in custody, the state paroled Adam, but he felt ill-equipped and completely unprepared for success outside of prison. He’d gone into the system as a teenager and emerged at age 21 without a clear sense of purpose nor a vision for his future.

Instead of pursuing his propose and finding a pathway to success, Adam returned to selling drugs and eventually committed another string of armed robberies. Those repeated bad decisions led a federal judge to impose a 213-year mandatory minimum sentence. Adam was only 24 years old when he received a sentence of “death in prison.”

High-Security Penitentiary:

Within hours of his transition into a high-security U.S. Penitentiary, other people in prison mentored Adam on how he should live. They gave him a knife, alcohol, and drugs to numb the pain. They offered the same message that permeated the state prison system of New Jersey:

“The best way to serve time,” they said, “would be to forget about the world outside and focus on his time inside.”

Early adjustment decisions led Adam to the Special Housing Unit. While in a solitary cell, he felt demoralized. Then, he had an epiphany: his choices had led him into the “prison within the prison,” and his decisions going forward would determine whether he spent the rest of his life in confinement or created a pathway that would lead him out.

Personal Development:

After several months, administrators released Adam from the Special Housing Unit. Rather than reverting to the behavior that had led to so much destruction in his life, he began committing to personal development. That strategy led to a series of opportunities. He created fitness classes and became a positive force within the penitentiary community.

Staff members noticed Adam’s transformation, but sentencing laws did not allow them to provide him with any hope for relief from a 213-year sentence. No laws nor policies yet existed to incentivize his pursuit of excellence.

Yet, with grit and determination, Adam continued along his transformative journey. Regardless of what the system offered, he understood that to reach his highest potential, he would need to work on personal development.

The Bureau of Prisons’ custody and classification policy included a list of Public Safety Factors (PSF). One PSF held that anyone with more than 25 years remaining to serve must stay in a high-security prison.

However, Administrators had some discretion. If they found a person worthy, they could recommend a management variable. A management variable would allow the administrators to waive the PSF and designate a person to a lower-security prison.

Adam was surprised when he learned that his case manager recommended transferring him to a medium-security prison.

When Adam transitioned to a medium-security prison, he continued to work toward differentiating himself in positive ways. For example:

- He created classes to teach others about fitness and nutrition,

- He studied spiritual leaders that helped him mature,

- He developed a relationship with Ro, a woman who had become his best friend and tireless advocate,

- He helped Ro to build Strong Prison Wives and Families, a platform to help other justice-impacted families,

- He began a self-directed study program to learn techniques for life coaching and personal development,

- He began networking with professors and students at a nearby university,

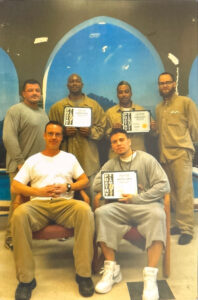

- He created a coaching program to help people evolve and commit to personal growth and development,

- He maintained a record free of any disciplinary infractions.

First Step Act:

The First Step Act did not exist when Adam began serving his sentence. By the time the law passed in 2018, Adam had served more than 20 years in prison. Rather than complaining about the sentence, he worked hard to differentiate himself. He wanted to prepare for success upon release—even though a release date would not come for 180+ years.

How does a person maintain hope in such circumstances?

He relied upon grit and determination.

By not complaining, Adam built a record of accomplishments others would find “extraordinary and compelling.” Although he did not qualify for Earned Time Credits under the original version of the First Step Act, he built a record that would persuade others to believe in his story.

Consider how Adam’s story adheres to the principles we teach in Preparing for Success after Prison:

Define Success:

Rather than focusing on what he could not control, Adam focused on what he could manage. Despite not having a release date that would come within his lifetime, he committed to personal development. He wanted to keep a clean disciplinary record and show that he could bring value to the lives of others.

Set Goals:

Adam could not control his release date. But he could work to create courses and persuade others of the value of his classes. He could lead hundreds and then thousands of people to work toward reaching their highest potential. Through those efforts, Adam could build a positive support group.

Attitude:

Adam made a 100% commitment to personal development. He did not work for certificates, a lower-bunk permit, or an extra bowl of cereal. He simply wanted to reach his highest potential.

Aspiration:

Despite not having a release date, Adam could see himself emerging successfully. He built a loving relationship with Ro and worked with her to contribute to the lives of others.

Action:

Adam took a series of incremental action steps ever since his epiphany in a segregation housing unit. When administrators released him from segregation, he focused on decisions that harmonized with personal development, and he refrained from any behavior that could bring him into conflict with others.

Accountability:

Rather than waiting for accolades from the system, Adam measured his progress for other reasons: He wanted to reach his highest potential. Those personal accountability metrics kept him on course.

Awareness:

Adam kept his head in the game. Success for him meant a daily commitment to personal development. He carved out his own path since he wanted to reach his highest potential regardless of external circumstances. Others took notice of him. Administrators recommended him for lower security levels, and Ro helped him connect with others in society that would play an influential role in Adam’s life.

Authenticity:

Adam did not fake his pursuit of excellence. Instead, he worked at it daily and invited others to hold him accountable. With the classes he created and the record of students he mentored, he built his own tools, tactics, and resources that he could leverage to advance his pursuit of excellence—as he defined excellence.

Achievement:

With a 213-year sentence to serve, Adam did not wait for the system to reward his efforts. Instead, he celebrated the little achievements that included: commitment to sobriety, completion of programs, a record free of disciplinary infractions.

Appreciation:

Adam lived in gratitude. Although he served a life sentence, he created opportunities to contribute to his community and serve others.

Success:

That pathway advanced Adam as a candidate for liberty. The incremental steps he took influenced lawyers to represent him pro bono. Influential leaders supported a campaign for Adam’s freedom.

Although some would say that Adam did not qualify for the First Step Act, he built an “extraordinary and compelling” record that persuaded a federal judge to grant him liberty through compassionate release.

Success in Society:

A judge released Adam from his 213-year sentence in 2020. Since then, he has become a community leader, using all the skills he learned in prison to build a life of meaning, relevance, and dignity. He married Ro, and together they brought their first child, Christian, into the world.

Adam works full-time as a community leader, helping justice-impacted people secure insurance while working on teaching strategies others can use to reach their highest potential. Together with his wife, Ro, Adam hosts the popular video podcast: Gritability